by Luigi Speranza for "Gli Operai" jlsperanza@aol.com

--- From Ricordi's edition (1910) of "Fanciulla":

NOTE. The Girl of the Golden West — a drama of love and of moral redemption against a dark and vast background of primitive characters and untrammelled nature — is an episode in this original period of American history. The action takes place in that period of California history which follows immediately upon the discovery made by the miner Marshall of the first nugget of gold, at Coloma, in January, 1848. An unbridled greed, an upheaval of all social order, a restless anarchy followed upon the news of this discovery. The United States, which in the same year, 1848, had annexed California, were engaged in internal wars; and, as yet undisturbed by the abnormal state of things, they were practically outside everything that occurred in the period of this work; the presence of their sheriff indicates a mere show of supremacy and political control. An early history of California, quoted by Belasco, says of this period: "In those strange days, people coming from God knows where joined forces in that far Western land, and, according to the rude custom cf the camp, their very names were soon

lost and unrecorded, and here they struggled, laughed, gambled, cursed, killed, loved, and worked out their strange destinies in a manner incredible to us of to-day. Of one thing only we are sure — they lived!' And here we have the atmosphere in which is evolved the drama of the three leading characters. The cgmp of the gold-seekers in the valley, and the Sierra Mountains ; the inhabitants of the spot coming down from the mountains, joining the goldseekers who come from every part of America, making common cause with them, sharing the same passions ; round this mixed and lawless folk a conglomeration of thieving and murderous gangs has sprung up as a natural outcome of this same lust of gold, and infests the highways, robbing the foreign goldseekers as well as those from the mountains; from the strenuous conflict between these two parties arises the application of a primitive justice of cruelty and rapacity.

This opera by Giacomo Puccini is founded upon the drama of the same name by David Belasco. The libretto is written by Carlo Zangarini and Guelfo Civinni It was first produced in New York in 1910. The scene is laid in a mining camp at the foot of Cloudy Mountains, in California, in the days of the gold fever, 1849 and 1850.

Act I. In the barroom of the "Polka" a number of miners are gathered and amongst them is Ranee, the sheriff. Ashby enters and says that after three months of tracking, his men are rounding up Ramerrez, and his band of Mexican "greasers." Minnie, a comely young woman, who has l)een brought up among the miners and since her father's death continues to run the business, enters in time to stop a fight between the sheriff and a miner who resented Ranee's boast that Minnie would soon be his wife. Ranee makes love to Minnie, but she repulses him, even showing him a revolver that she carries. After a time a stranger api^cars. He gives his name as Dick Johnson from Sacramento, and when the sheriff threatens him, Minnie acknowledges that she has met him licfore. She and the stranger recall their chance meeting on the road when each fell in love with the other, and Johnson (who is no other tl:an Ramerrez, the outlaw, and who has come to rob the saloon, knowing that the miners leave their gold in Minnie's charge) finds himself so attracted by the girl that he relinquishes his plan. When Minnie has gone with him and the miners into the dance hall, .Ashby's men bring in Jose Castro. They are for hanging him, and Castro, though he sees his chief's saddle and thinks him captured, soon finds from the talk that Ramerrez is still free, and offers to conduct them to him. The miners go off with the sheriff and Ashby's men to seize the outlaw, leaving their barrel of gold in Minnie's charge, with only Nick and Billy to protect her and it. Nick reports that a greaser is sulking around, and Johnson knows that his men are only awaiting his whistle to come and seize the gold. Minnie declares valiantly that he who takes the gold will have to kill her first, and he admires her spirit. She invites him to call on her in her cabin after the miners come back, and he. accepting the invitation, goes out.

Act II. At Minnie's dwelling Wowkle is sitting on the floor before the fire rocking her baby in her arms. Billy comes in and Minnie soon follows. She puts on what finery she possesses and* when Johnson arrives entertains him graciously. They both acknowledge their love, and when a severe snowstorm comes up Minnie invites him to remain for the night. Pistol shots are heard and Johnson, knowing himself to be in grave danger, determines to stay with Minnie and vows that he will never give her up. Johnson is lying on Minnie's bed and she is resting on the hearth rug when shouts are heard without, and Nick hails Minnie. She insists that Johnson hide, and then she admits Nick, Ranee, Ashby and some of the miners. They tell her that Dick Johnson is Ramerrez, and is near, and that they were worried about her. They say also that Johnson came to the saloon to take their gold, though he left without it, which they cannot understand. She is overwhelmed by their revelations, especially when Johnson's photograph, obtained from a notorious woman at a nearby ranch, is shown her. She sends the men ofif and will not listen to having any one stay with her. When they are gone she confronts Johnson with the photograph and he confesses who he is and tells her how he was brought up to the life of an outlaw. Minnie cannot forgive him for deceiving her when she gave him her

love, and she sends him ofif. Johnson goes out, desperate and willing to die. A shot is heard and Minnie opens the door, drags him in wounded, and hides him in the loft. Ranee enters and Minnie has almost convinced him that the outlaw escaped and is not there, when a drop of blood falls on his hand. He drags the wounded man down from the loft. Minnie, knowing that the sherifiF has the gambler's passion, offers to play a game of poker with him, her life and Johnson's to be the stake. If she loses she will marry him and he may do what he will with Johnson. They play while Johnson lies unconscious near, and Ranee is winning when Minnie clearly cheats and so wins the game. Ranee, dumbfounded, but true to his word, goes out.

Act III. On the edge of the great Californian forest in the early dawn, Ranee, Ashby and Nick are waiting. Ranee tells of his chagrin that Johnson's wound was not fatal, and that Minnie had nursed him back to life at her cabin. Ashby's men come on the scene, having captured Johnson after an exciting chase. He is brought in, bound and wounded and his clothing torn. The men gather about him like animals about their prey, and taunt him savagely. Johnson confronts them defiantly, even when they name many of the robberies and murders that he and his gang have committed. As they are about to hang him he asks one favor — that they will never tell Minnie how he died. At the last moment Minnie dashes in on horseback. She places herself in front of Johnson and presents her pistol to the crowd, and in spite of Ranee's orders no one dares to push her aside and pull the noose taut. Minnie appeals to them, and at last, in spite of Ranee the miners cut the noose and restore Johnson to Minnie. The two go ofif together amid the affectionate farewells of the men.

Thursday, December 2, 2010

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Analytic Table of Contents for "Chapters of Opera" -- an excellent book.

by Luigi Speranza for "Gli Operai" jlsperanza@aol.com

Chapters of Opera, by Krehbiel

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION OF OPERA IN NEW YORK

1. The Introduction of Italian Opera in New York

2. English Ballad Operas and Adaptations from French and Italian Works

3. Hallam's Comedians and "The Beggar's Opera"

4. The John Street Theater and Its Early Successors

5. Italian Opera's First Home

6. Manuel Garcia

7. The New Park Theater and Some of Its Rivals

8. Malibran and English Opera

9. The Bowery Theater, Richmond Hill, Niblo's and Castle Gardens

CHAPTER II

EARLY THEATERS, MANAGERS, AND SINGERS

2.1 Of the Building of Opera Houses

2.2. A Study of Influences

2. 3. The First Italian Opera House in New York

Early Impresarios and Singers

Da Ponte, Montressor, Rivafinoli

Signorina Pedrotti and Fornasari

Why Do Men Become Opera-Managers?

Addison and Italian Opera

The Vernacular Triumphant

CHAPTER III

THE FIRST ITALIAN COMPANY

Manuel del Popolo Vicente Garcia

"Il Barbiere di Siviglia"

Signorina Maria Garcia's Unfortunate Marriage

Lorenzo da Ponte

His Hebraic Origin and Checkered Career

"Don Giovanni"

An Appeal in Behalf of Italian Opera

CHAPTER IV

HOUSES BUILT FOR OPERA

More Opera Houses

Palmo's and the Astor Place

Signora Borghese and the Distressful Vocal Wabble

Antognini and Cinti-Damoreau

An Orchestral Strike

Advent of the Patti Family

Don Francesco Marty y Torrens and His Havanese Company

Opera Gowns Fifty Years Ago

Edward and William Henry Fry

Horace Greeley and His Musical Critic

James H. Hackett and William Niblo

Tragic Consequences of Canine Interference

Goethe and a Poodle

A Dog-Show and the Astor Place Opera House

CHAPTER V: MARETZEK, HIS RIVALS AND SINGERS

Max Maretzek

His Managerial Career

Some Anecdotes

"Crotchets and Quavers"

His Rivals and Some of His Singers

Bernard Ullmann

Marty Again

Bottesini and Arditi

Steffanone

Bosio

Tedesco

Salvi

Bettini

Badiali

Marini

CHAPTER VI: THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF MUSIC

Operatic Warfare Half a Century Ago

The Academy of Music and Its Misfortunes

A Critic's Opera and His Ideals

A Roster of American Singers

Grisi and Mario

Annie Louise Cary

Ole Bull as Manager

Piccolomini and Réclame

Adelina Patti's Début and an Anniversary Dinner Twenty-five

Years Later

A Kiss for Maretzek

CHAPTER VII: MAPLESON AND OTHER IMPRESARIOS

Colonel James H. Mapleson

A Diplomatic Manager

His Persuasiveness

How He Borrowed Money from an Irate Creditor

Maurice Strakosch

Musical Managers

Pollini

Sofia Scalchi and Annie Louise Cary Again

Campanini and His Beautiful Attack

Brignoli

His Appetite and Superstition

CHAPTER VIII: THE METROPOLITAN OPERA HOUSE

The Academy's Successful Rival

Why It Was Built

The Demands of Fashion

Description of the Theater

War between the Metropolitan and the Academy of Music

Mapleson and Abbey

The Rival Forces

Patti and Nilsson

Gerster and Sembrich

A Costly Victory

CHAPTER IX: FIRST SEASON AT THE METROPOLITAN

The First Season at the Metropolitan Opera House

Mr. Abbey's Singers

Gounod's "Faust" and Christine Nilsson

Marcella Sembrich and Her Versatility

Sofia Scalchi

Signor Kaschmann

Signor Stagno

Ambroise Thomas's "Mignon"

Madame Fursch-Madi

Ponchielli's "La Gioconda"

CHAPTER X: OPERATIC REVOLUTIONS

The Season 1883-1884 at the Academy of Music

Lillian Nordica's American Début

German Opera Introduced at the Metropolitan Opera House

Parlous State of Italian Opera in London and on the Continent

Dr. Leopold Damrosch and His Enterprise

The German Singers

Amalia Materna

Marianne Brandt

Marie Schroeder-Hanfstängl

Anton Schott, the Military Tenor

Von Bülow's Characterization: "A Tenor is a Disease"

CHAPTER X: GERMAN OPERA AT THE METROPOLITAN

First German Season

Death Struggles of Italian Opera at the Academy

Adelina Patti and Her Art

Features of the German Performances

"Tannhäuser"

Marianne Brandt in Beethoven's Opera

"Der Freischütz"

"Masaniello"

Materna in "Die Walküre"

Death of Dr. Damrosch

CHAPTER XII: END OF ITALIAN OPERA AT THE ACADEMY

The Season 1885-1886

End of the Mapleson Régime at the Academy of Music

Alma Fohström

The American Opera Company

German Opera in the Bowery

A Tenor Who Wanted to be Manager of the Metropolitan Opera House

The Coming of Anton Seidl

His Early Career

Lilli Lehmann

A Broken Contract

Unselfish Devotion to Artistic Ideals

Max Alvary

Emil Fischer

CHAPTER XIII: WAGNER HOLDS THE METROPOLITAN

Second and Third German Seasons

The Period 1885-1888

More about Lilli Lehmann

Goldmark's "Queen of Sheba"

First Performance of Wagner's "Meistersinger"

Patti in Concert and Opera

A Flash in the Pan at the Academy of Music

The Transformed American Opera Company

Production of Rubinstein's "Nero"

An Imperial Operatic Figure

First American Performance of "Tristan und Isolde"

Albert Niemann and His Characteristics

His Impersonation of Siegmund

Anecdotes

A Triumph for "Fidelio"

CHAPTER XIV: WAGNERIAN HIGH TIDE

Wagnerian High Tide at the Metropolitan Opera House

1887-1890

Italian Low Water Elsewhere

Rising of the Opposition

Wagner's "Siegfried"

Its Unconventionality

"Götterdämmerung"

"Der Trompeter von Säkkingen"

"Euryanthe"

"Ferdinand Cortez"

"Der Barbier von Bagdad"

Italo Campanini and Verdi's "Otello"

Patti and Italian Opera at the Metropolitan Opera House

CHAPTER XV: END OF THE GERMAN PERIOD

End of the German Period

1890-1891

Some Extraordinary Novelties

Franchetti's "Asrael"

"Der Vasall von Szigeth"

A Royal Composer, His Opera and His Distribution of Decorations

"Diana von Solange"

Financial Salvation through Wagner

Italian Opera Redivivus

Ill-mannered Box-holders

Wagnerian Statistics

CHAPTER XVI: ITALIAN OPERA AGAIN AT THE METROPOLITAN

The Season 1891-1892

Losses of the Stockholders of the Metropolitan Opera House Company

Return to Italian Opera

Mr. Abbey's Expectations

Sickness of Lilli Lehmann

The De Reszke Brothers and Lassalle

Emma Eames

Début of Marie Van Zandt

"Cavalleria Rusticana"

Fire Damages the Opera House

Reorganization of the Owning Company

CHAPTER XVII: THE ADVENT OF MELBA AND CALVÉ

An Interregnum

Changes in the Management

Rise and Fall of Abbey, Schoeffel, and Grau

Death of Henry E. Abbey

His Career

Season 1893-1894

Nellie Melba

Emma Calvé

Bourbonism of the Parisians

Massenet's "Werther"

1894-1895

A Breakdown on the Stage

"Elaine"

Sybil Sanderson and "Manon"

Shakespearian Operas

Verdi's "Falstaff"

CHAPTER XVIII: UPRISING IN FAVOR OF GERMAN OPERA

The Public Clamor for German Opera

Oscar Hammerstein and His First Manhattan Opera House

Rivalry between Anton Seidl and Walter Damrosch

The Latter's Career as Manager

Wagner Triumphant

German Opera Restored at the Metropolitan

"The Scarlet Letter"

"Mataswintha"

"Hänsel und Gretel" in English

Jean de Reszke and His Influence

Mapleson for the Last Time

"Andrea Chenier"

Madame Melba's Disastrous Essay with Wagner

"Le Cid"

Metropolitan Performances 1893-1897

CHAPTER XIX: BEGINNING OF THE GRAU PERIOD

Beginning of the Grau Period

Death of Maurice Grau

His Managerial Career

An Interregnum at the Metropolitan Opera House Filled by

Damrosch and Ellis

Death of Anton Seidl

His Funeral

Characteristic Traits

"La Bohème"

1898-1899

"Ero e Leandro" and Its Composer

CHAPTER XX: NEW SINGERS AND OPERAS

Closing Years of Mr. Grau's Régime

Traits in the Manager's Character

Débuts of Alvarez, Scotti, Louise Homer, Lucienne Bréval and

Other Singers

Ternina and "Tosca"

Reyer's "Salammbô"

Gala Performance for a Prussian Prince

"Messaline"

Paderewski's "Manru"

"Der Wald"

Performances in the Grau Period

CHAPTER XXI: HEINRICH CONRIED AND "PARSIFAL"

Beginning of the Administration of Heinrich Conried

Season 1903-1904

Mascagni's American Fiasco

"Iris" and "Zanetto"

Woful Consequences of Depreciating American Conditions

Mr. Conried's Theatrical Career

His Inheritance from Mr. Grau

Signor Caruso

The Company Recruited

The "Parsifal" Craze

CHAPTER XXII: END OF CONRIED'S ADMINISTRATION

Conried's Administration Concluded

1905-1908

Visits from Humperdinck and Puccini

The California Earthquake

Madame Sembrich's Generosity to the Suffering Musicians

"Madama Butterfly"

"Manon Lescaut"

"Fedora"

Production and Prohibition of "Salome"

A Criticism of the Work

"Adriana Lecouvreur"

A Table of Performances

CHAPTER XXIII: HAMMERSTEIN AND HIS OPERA HOUSE

Oscar Hammerstein Builds a Second Manhattan Opera House

How the Manager Put His Doubters to Shame

His Earlier Experiences as Impresario

Cleofonte Campanini

A Zealous Artistic Director and Ambitious Singers

A Surprising Record but No Novelties in the First Season

Melba and Calvé as Stars

The Desertion of Bonci

Quarrels about Puccini's "Bohéme"

List of Performances

CHAPTER XXIV: A BRILLIANT SEASON AT THE MANHATTAN

Hammerstein's Second Season

Amazing Promises but More Amazing Achievements

Mary Garden and Maurice Renaud

Massenet's "Thaïs," Charpentier's "Louise"

Giordano's "Siberia" and Debussy's "Pelléas et Mélisande" Performed for

the First Time in America

Revival of Offenbach's "Les Contes d'Hoffmann," "Crispino e la Comare"

of the Ricci Brothers, and Giordano's "Andrea Chenier"

The Tetrazzini Craze

Repertory of the Season

------

Index of Names.

There is a second volume to this, "Chapters of Opera," ii.

Chapters of Opera, by Krehbiel

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION OF OPERA IN NEW YORK

1. The Introduction of Italian Opera in New York

2. English Ballad Operas and Adaptations from French and Italian Works

3. Hallam's Comedians and "The Beggar's Opera"

4. The John Street Theater and Its Early Successors

5. Italian Opera's First Home

6. Manuel Garcia

7. The New Park Theater and Some of Its Rivals

8. Malibran and English Opera

9. The Bowery Theater, Richmond Hill, Niblo's and Castle Gardens

CHAPTER II

EARLY THEATERS, MANAGERS, AND SINGERS

2.1 Of the Building of Opera Houses

2.2. A Study of Influences

2. 3. The First Italian Opera House in New York

Early Impresarios and Singers

Da Ponte, Montressor, Rivafinoli

Signorina Pedrotti and Fornasari

Why Do Men Become Opera-Managers?

Addison and Italian Opera

The Vernacular Triumphant

CHAPTER III

THE FIRST ITALIAN COMPANY

Manuel del Popolo Vicente Garcia

"Il Barbiere di Siviglia"

Signorina Maria Garcia's Unfortunate Marriage

Lorenzo da Ponte

His Hebraic Origin and Checkered Career

"Don Giovanni"

An Appeal in Behalf of Italian Opera

CHAPTER IV

HOUSES BUILT FOR OPERA

More Opera Houses

Palmo's and the Astor Place

Signora Borghese and the Distressful Vocal Wabble

Antognini and Cinti-Damoreau

An Orchestral Strike

Advent of the Patti Family

Don Francesco Marty y Torrens and His Havanese Company

Opera Gowns Fifty Years Ago

Edward and William Henry Fry

Horace Greeley and His Musical Critic

James H. Hackett and William Niblo

Tragic Consequences of Canine Interference

Goethe and a Poodle

A Dog-Show and the Astor Place Opera House

CHAPTER V: MARETZEK, HIS RIVALS AND SINGERS

Max Maretzek

His Managerial Career

Some Anecdotes

"Crotchets and Quavers"

His Rivals and Some of His Singers

Bernard Ullmann

Marty Again

Bottesini and Arditi

Steffanone

Bosio

Tedesco

Salvi

Bettini

Badiali

Marini

CHAPTER VI: THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF MUSIC

Operatic Warfare Half a Century Ago

The Academy of Music and Its Misfortunes

A Critic's Opera and His Ideals

A Roster of American Singers

Grisi and Mario

Annie Louise Cary

Ole Bull as Manager

Piccolomini and Réclame

Adelina Patti's Début and an Anniversary Dinner Twenty-five

Years Later

A Kiss for Maretzek

CHAPTER VII: MAPLESON AND OTHER IMPRESARIOS

Colonel James H. Mapleson

A Diplomatic Manager

His Persuasiveness

How He Borrowed Money from an Irate Creditor

Maurice Strakosch

Musical Managers

Pollini

Sofia Scalchi and Annie Louise Cary Again

Campanini and His Beautiful Attack

Brignoli

His Appetite and Superstition

CHAPTER VIII: THE METROPOLITAN OPERA HOUSE

The Academy's Successful Rival

Why It Was Built

The Demands of Fashion

Description of the Theater

War between the Metropolitan and the Academy of Music

Mapleson and Abbey

The Rival Forces

Patti and Nilsson

Gerster and Sembrich

A Costly Victory

CHAPTER IX: FIRST SEASON AT THE METROPOLITAN

The First Season at the Metropolitan Opera House

Mr. Abbey's Singers

Gounod's "Faust" and Christine Nilsson

Marcella Sembrich and Her Versatility

Sofia Scalchi

Signor Kaschmann

Signor Stagno

Ambroise Thomas's "Mignon"

Madame Fursch-Madi

Ponchielli's "La Gioconda"

CHAPTER X: OPERATIC REVOLUTIONS

The Season 1883-1884 at the Academy of Music

Lillian Nordica's American Début

German Opera Introduced at the Metropolitan Opera House

Parlous State of Italian Opera in London and on the Continent

Dr. Leopold Damrosch and His Enterprise

The German Singers

Amalia Materna

Marianne Brandt

Marie Schroeder-Hanfstängl

Anton Schott, the Military Tenor

Von Bülow's Characterization: "A Tenor is a Disease"

CHAPTER X: GERMAN OPERA AT THE METROPOLITAN

First German Season

Death Struggles of Italian Opera at the Academy

Adelina Patti and Her Art

Features of the German Performances

"Tannhäuser"

Marianne Brandt in Beethoven's Opera

"Der Freischütz"

"Masaniello"

Materna in "Die Walküre"

Death of Dr. Damrosch

CHAPTER XII: END OF ITALIAN OPERA AT THE ACADEMY

The Season 1885-1886

End of the Mapleson Régime at the Academy of Music

Alma Fohström

The American Opera Company

German Opera in the Bowery

A Tenor Who Wanted to be Manager of the Metropolitan Opera House

The Coming of Anton Seidl

His Early Career

Lilli Lehmann

A Broken Contract

Unselfish Devotion to Artistic Ideals

Max Alvary

Emil Fischer

CHAPTER XIII: WAGNER HOLDS THE METROPOLITAN

Second and Third German Seasons

The Period 1885-1888

More about Lilli Lehmann

Goldmark's "Queen of Sheba"

First Performance of Wagner's "Meistersinger"

Patti in Concert and Opera

A Flash in the Pan at the Academy of Music

The Transformed American Opera Company

Production of Rubinstein's "Nero"

An Imperial Operatic Figure

First American Performance of "Tristan und Isolde"

Albert Niemann and His Characteristics

His Impersonation of Siegmund

Anecdotes

A Triumph for "Fidelio"

CHAPTER XIV: WAGNERIAN HIGH TIDE

Wagnerian High Tide at the Metropolitan Opera House

1887-1890

Italian Low Water Elsewhere

Rising of the Opposition

Wagner's "Siegfried"

Its Unconventionality

"Götterdämmerung"

"Der Trompeter von Säkkingen"

"Euryanthe"

"Ferdinand Cortez"

"Der Barbier von Bagdad"

Italo Campanini and Verdi's "Otello"

Patti and Italian Opera at the Metropolitan Opera House

CHAPTER XV: END OF THE GERMAN PERIOD

End of the German Period

1890-1891

Some Extraordinary Novelties

Franchetti's "Asrael"

"Der Vasall von Szigeth"

A Royal Composer, His Opera and His Distribution of Decorations

"Diana von Solange"

Financial Salvation through Wagner

Italian Opera Redivivus

Ill-mannered Box-holders

Wagnerian Statistics

CHAPTER XVI: ITALIAN OPERA AGAIN AT THE METROPOLITAN

The Season 1891-1892

Losses of the Stockholders of the Metropolitan Opera House Company

Return to Italian Opera

Mr. Abbey's Expectations

Sickness of Lilli Lehmann

The De Reszke Brothers and Lassalle

Emma Eames

Début of Marie Van Zandt

"Cavalleria Rusticana"

Fire Damages the Opera House

Reorganization of the Owning Company

CHAPTER XVII: THE ADVENT OF MELBA AND CALVÉ

An Interregnum

Changes in the Management

Rise and Fall of Abbey, Schoeffel, and Grau

Death of Henry E. Abbey

His Career

Season 1893-1894

Nellie Melba

Emma Calvé

Bourbonism of the Parisians

Massenet's "Werther"

1894-1895

A Breakdown on the Stage

"Elaine"

Sybil Sanderson and "Manon"

Shakespearian Operas

Verdi's "Falstaff"

CHAPTER XVIII: UPRISING IN FAVOR OF GERMAN OPERA

The Public Clamor for German Opera

Oscar Hammerstein and His First Manhattan Opera House

Rivalry between Anton Seidl and Walter Damrosch

The Latter's Career as Manager

Wagner Triumphant

German Opera Restored at the Metropolitan

"The Scarlet Letter"

"Mataswintha"

"Hänsel und Gretel" in English

Jean de Reszke and His Influence

Mapleson for the Last Time

"Andrea Chenier"

Madame Melba's Disastrous Essay with Wagner

"Le Cid"

Metropolitan Performances 1893-1897

CHAPTER XIX: BEGINNING OF THE GRAU PERIOD

Beginning of the Grau Period

Death of Maurice Grau

His Managerial Career

An Interregnum at the Metropolitan Opera House Filled by

Damrosch and Ellis

Death of Anton Seidl

His Funeral

Characteristic Traits

"La Bohème"

1898-1899

"Ero e Leandro" and Its Composer

CHAPTER XX: NEW SINGERS AND OPERAS

Closing Years of Mr. Grau's Régime

Traits in the Manager's Character

Débuts of Alvarez, Scotti, Louise Homer, Lucienne Bréval and

Other Singers

Ternina and "Tosca"

Reyer's "Salammbô"

Gala Performance for a Prussian Prince

"Messaline"

Paderewski's "Manru"

"Der Wald"

Performances in the Grau Period

CHAPTER XXI: HEINRICH CONRIED AND "PARSIFAL"

Beginning of the Administration of Heinrich Conried

Season 1903-1904

Mascagni's American Fiasco

"Iris" and "Zanetto"

Woful Consequences of Depreciating American Conditions

Mr. Conried's Theatrical Career

His Inheritance from Mr. Grau

Signor Caruso

The Company Recruited

The "Parsifal" Craze

CHAPTER XXII: END OF CONRIED'S ADMINISTRATION

Conried's Administration Concluded

1905-1908

Visits from Humperdinck and Puccini

The California Earthquake

Madame Sembrich's Generosity to the Suffering Musicians

"Madama Butterfly"

"Manon Lescaut"

"Fedora"

Production and Prohibition of "Salome"

A Criticism of the Work

"Adriana Lecouvreur"

A Table of Performances

CHAPTER XXIII: HAMMERSTEIN AND HIS OPERA HOUSE

Oscar Hammerstein Builds a Second Manhattan Opera House

How the Manager Put His Doubters to Shame

His Earlier Experiences as Impresario

Cleofonte Campanini

A Zealous Artistic Director and Ambitious Singers

A Surprising Record but No Novelties in the First Season

Melba and Calvé as Stars

The Desertion of Bonci

Quarrels about Puccini's "Bohéme"

List of Performances

CHAPTER XXIV: A BRILLIANT SEASON AT THE MANHATTAN

Hammerstein's Second Season

Amazing Promises but More Amazing Achievements

Mary Garden and Maurice Renaud

Massenet's "Thaïs," Charpentier's "Louise"

Giordano's "Siberia" and Debussy's "Pelléas et Mélisande" Performed for

the First Time in America

Revival of Offenbach's "Les Contes d'Hoffmann," "Crispino e la Comare"

of the Ricci Brothers, and Giordano's "Andrea Chenier"

The Tetrazzini Craze

Repertory of the Season

------

Index of Names.

There is a second volume to this, "Chapters of Opera," ii.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

Why we prefer a simple "Orfeo"

Sartorio's "Orfeo", rather:

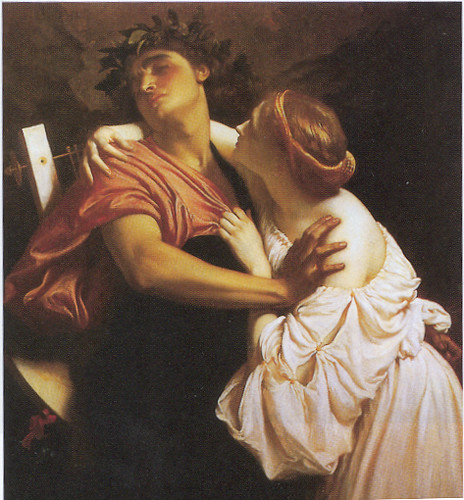

The plot is extremely complicated. In Aureli and Sartorio's version of the story, Aristaeus is Orpheus's brother and he too is in love with Eurydice, which makes Orpheus jealous. Aristaeus rejects the love of Autonoe who disguises herself as a gypsy to be near him and enlists the help of Achilles and Hercules. The jealous Orpheus plans to have Eurydice murdered in a forest but Eurydice dies when she steps on a snake while trying to flee Aristaeus. Orpheus sets off for the underworld to bring Eurydice back to life. Pluto, the ruler of the underworld, is won over by his singing and releases Eurydice on condition that Orpheus does not look at her before they have reached the land of the living. But Orpheus turns roundd and Eurydice is lost again. Aristaeus finally accepts the love of Autonoe and the two are married.

The plot is extremely complicated. In Aureli and Sartorio's version of the story, Aristaeus is Orpheus's brother and he too is in love with Eurydice, which makes Orpheus jealous. Aristaeus rejects the love of Autonoe who disguises herself as a gypsy to be near him and enlists the help of Achilles and Hercules. The jealous Orpheus plans to have Eurydice murdered in a forest but Eurydice dies when she steps on a snake while trying to flee Aristaeus. Orpheus sets off for the underworld to bring Eurydice back to life. Pluto, the ruler of the underworld, is won over by his singing and releases Eurydice on condition that Orpheus does not look at her before they have reached the land of the living. But Orpheus turns roundd and Eurydice is lost again. Aristaeus finally accepts the love of Autonoe and the two are married.

Recordings of Landi's "Orfeo"

La morte d'Orfeo Elwes, Koslowski, Cordier, van der Kamp, Tragicomedia, conducted by Stephen Stubbs (Accent, 1987)

La morte d'Orfeo Auvity, Laurens, Visse, van Elsacker, Guillon, Bucher, Akadêmia, conducted by Françoise Lasserre (Zig Zag Territoires, 2007)

La morte d'Orfeo Auvity, Laurens, Visse, van Elsacker, Guillon, Bucher, Akadêmia, conducted by Françoise Lasserre (Zig Zag Territoires, 2007)

comparing "Che faro senza Euridice" with Monteverdi -- on DVD

Check with DVD Monteverdi's "Orfeo" for his reaction upon the vanishing of Euridice. Also with Baker -- Glyndebourne DVD.

Recordings of Caccini's opera, "Orfeo ed Euridice" (1600)

Euridice Soloists, Rennes Chorus and Orchestra, conducted by Rodrigo de Zayas (Arion, 1980)

L'Euridice Scherzi Musicali, Nicolas Achten (Ricercar, 2008) [1]

L'Euridice Scherzi Musicali, Nicolas Achten (Ricercar, 2008) [1]

Dates of some Italian "Orfeos" from 1600 onwards

1600. Jacopo Peri, "Orfeo ed Euridice". Performed at Palazzo Pitti, Firenze. The first genuine opera whose music survives to this day. The role of Orfeo played by Peri and in later performances by Basi, who will create the role in Monteverdi's better known version, in Mantova.

1602 - Giulio Caccini, "Orfeo ed Euridice". Caccini's daughter had played Euridice in Peri's version. Caccini managed to publish his own opera before Peri, but it was not performed till 1602.

1607 - Claudio Monteverdi – Monteverdi's "Orfeo", widely regarded as the first operatic masterwork.

1616 - Domenico Belli - "Orfeo dolente".

1619 - Stefano Landi – "La morte d'Orfeo"

1647 - Luigi Rossi – "Orfeo".

1654 - Carlo d'Aquino – Orfeo

1672 - Antonio Sartorio – Orfeo

1676 - Giuseppe di Dia – Orfeo

1677 - Francesco della Torre – Orfeo

1683 - Antonio Draghi – La lira d' Orfeo

1689 - Bernardo Sabadini – Orfeo

1690 - Luigi Lulli – Orfeo.

1699 - André Campra – Orfeo nell'inferni

1715 - Johann Joseph Fux – Orfeo ed Euridice

1749 - Giovanni Alberto Ristori – I lamenti d'Orfeo

1762 - Christoph Willibald Gluck – Orfeo ed Euridice. Contains: "Che faro senza Euridice?", also set by Bertoni. Published by Ricordi 1889. Recorded by Tito Schipa with the Milano orchestra "Grammofono" and by Pavarotti in concert (to piano accompaniment).

1775 - Antonio Tozzi – Orfeo ed Euridice

1776 - Ferdinando Bertoni – Orfeo ed Euridice (to the same libretto as Gluck's more famous work)

1781 - Luigi Torelli – Orfeo

1789 - Vittorio Trento – Orfeo negli Elisi

1791 - Joseph Haydn – L'anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice. On DVD with Bertoli.

1791 - Ferdinando Paer – Orfeo.

1796 - Luigi Lamberti – Orfeo

1796 - Francesco Morolin – Orfeo ed Euridice

1814 - Marchese Francesco Sampieri – Orfeo.

1858 - Jacques Offenbach - Orphée aux enfers. On DVD.

1925 - Gian Francesco Malipiero – L'Orfeide.

1932 - Alfredo Casella – La favola d'Orfeo, chamber opera after Poliziano's L'Orfeo

1996 - Lorenzo Ferrero - Orfeo, musical action in one act, libretto by Lorenzo Ferrero and Dario Del Corno, premiered at the Teatro Filarmonico

1602 - Giulio Caccini, "Orfeo ed Euridice". Caccini's daughter had played Euridice in Peri's version. Caccini managed to publish his own opera before Peri, but it was not performed till 1602.

1607 - Claudio Monteverdi – Monteverdi's "Orfeo", widely regarded as the first operatic masterwork.

1616 - Domenico Belli - "Orfeo dolente".

1619 - Stefano Landi – "La morte d'Orfeo"

1647 - Luigi Rossi – "Orfeo".

1654 - Carlo d'Aquino – Orfeo

1672 - Antonio Sartorio – Orfeo

1676 - Giuseppe di Dia – Orfeo

1677 - Francesco della Torre – Orfeo

1683 - Antonio Draghi – La lira d' Orfeo

1689 - Bernardo Sabadini – Orfeo

1690 - Luigi Lulli – Orfeo.

1699 - André Campra – Orfeo nell'inferni

1715 - Johann Joseph Fux – Orfeo ed Euridice

1749 - Giovanni Alberto Ristori – I lamenti d'Orfeo

1762 - Christoph Willibald Gluck – Orfeo ed Euridice. Contains: "Che faro senza Euridice?", also set by Bertoni. Published by Ricordi 1889. Recorded by Tito Schipa with the Milano orchestra "Grammofono" and by Pavarotti in concert (to piano accompaniment).

1775 - Antonio Tozzi – Orfeo ed Euridice

1776 - Ferdinando Bertoni – Orfeo ed Euridice (to the same libretto as Gluck's more famous work)

1781 - Luigi Torelli – Orfeo

1789 - Vittorio Trento – Orfeo negli Elisi

1791 - Joseph Haydn – L'anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice. On DVD with Bertoli.

1791 - Ferdinando Paer – Orfeo.

1796 - Luigi Lamberti – Orfeo

1796 - Francesco Morolin – Orfeo ed Euridice

1814 - Marchese Francesco Sampieri – Orfeo.

1858 - Jacques Offenbach - Orphée aux enfers. On DVD.

1925 - Gian Francesco Malipiero – L'Orfeide.

1932 - Alfredo Casella – La favola d'Orfeo, chamber opera after Poliziano's L'Orfeo

1996 - Lorenzo Ferrero - Orfeo, musical action in one act, libretto by Lorenzo Ferrero and Dario Del Corno, premiered at the Teatro Filarmonico

A different setting to "Che faro senza Euridice?" first heard in Venice

Bertoni's "Orfeo" opened in Venice, at the Teatro San Benedetto, 1776), based on the same libretto of Ranieri de' Calzabigi of the work of Gluck.

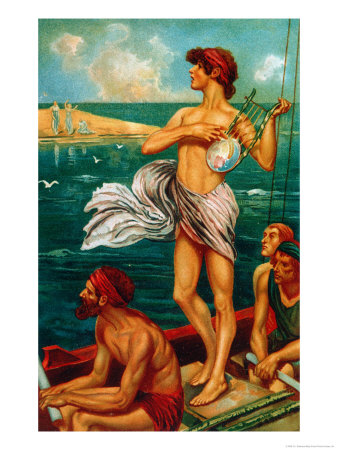

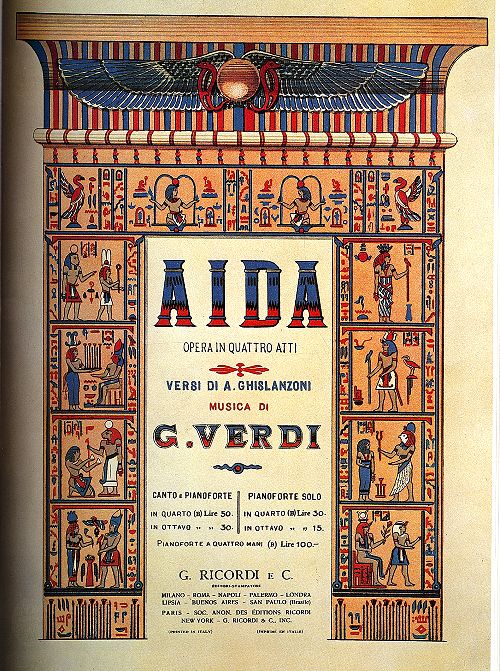

possibly the best image, and coloured too---for songbook

possibly the best image, and coloured, too.

Che farò senza Euridice!

by Luigi Speranza for "Gli Operai" jlsperanza@aol.com

I

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Rien n'égale mon malheur.

Che farò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che farò senza il mio ben? Rien n'égale mon malheur.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Je succombe à ma douleur.

II

(a)

Euridice! Euridice! Eurydice! Eurydice!

Oh Dio, rispondi! Réponds! Quel supplice!

Rispondi! Réponds-moi!

(b)

Io son pure il tuo fedel. C'est ton époux, ton époux fidèle.

Io son pure il tuo fedel. Entends ma voix qui t'appelle,

il tuo fedel. ma voix qui t'appelle.

III

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Rien m'égale mon malheur.

Che farò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che farò senza il mio ben? Rien m'égale mon malheur.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Je succombe à ma doleur.

IV

(a)

Euridice! Euridice! Euydice! Eurydice!

(b)

Ah, non m'avanza Mortel silence!

Più soccorso, più speranza Vaine esperance! Quelle souffrance!

Né dal mondo né dal ciel. Quel tourment déchire mon cœur.

V

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Rien m'egale mon malheur.

Che fafò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

che faro senza il mio ben Rien m'égale mon malheur.

Che farò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che farò senza il mio ben? J'ai succombe à ma doleur,

Senza il mio ben? à ma doleur,

Senza il mio ben? à ma doleur.

NOTES.

For what is worth (a lot, :) -- since you won't find this online, this far!) the strict comparison, line-by-line of Ranieri de' Calzabigi and Moline's translation, which Ricordi ignored when he omitted it in the 1889 edition. One may do with a strict analysis of 'performative' acts. The Italian version is all about 'rhetorical' questions, almost -- although not quite. Some say that Orfeo is a controversial figure. So, when he says, "What shall I do WITHOUT Eurydice?" he may MEAN it. As it happens, he became so disilussioned with women after this disgrace that it provoked the reaction by the Furies who dismember him. I understand this was the original Monteverdi ending which he was forced to adapt for the wedding of de Medici, or something.

lines 1-2.

So, to the 'question', "Che faro, dove andro?", the French offers a statement: "J'ai perdu mon Eurydice". (In fact, this has been parodied, elsewhere, as "J'ai TROUVE mon Eurydice"). Again, the second 'rhetoric' question ("Where will I go without my good?") becomes another statement, however spiritual, "Rien n'egale mon malheur".

lines 3-4.

The loveliness of the interrupted questions in the Italian, "What shall I do, where shall I go" (che faro, dove andro) are turned into 'exclamatives' in French. In fact, I find one exclamative too many in the French. So the first here are "Sort cruel!" corresponding to the abbreviated question, "Che faro", and the proper exclamative, "Quelle rigueur" for the "dove andro".

line 5.

The next divergence is the introduction of a NEW proposition in the first 'stanza', 'Je succombe a ma doleur' in the French. The Italian just does with a repetition of previous, er, questions, notably the second: "Dove andro senza il mio ben?".

line 5.

Now, we can examine the rhyme in the first stanza. The French manages with a perfect consonant rhyme in a trio: malheur--rigueur--douleur. Which is unavailable in Italian, which merely has, but I love it, still, 'mio ben', rhyiming with 'mio ben', rhyming with 'mio ben'!

line 6-7.

In the second 'stanza', Moline manages to introduce 'suplice' to rhyme with "Eurydice" of the 'vocative' (one vocative too many, for my taste, in this arietta). Instead, the Italian, rather clumsily, introduces a different emphatic, "Oh Dio", which sort of puts me off slightly. I do tend to use this exclamative often, but without MEANING it. How many of us, do say, "Oh my God" withOUT meaning it. I think this is the case with Orfeo. In any case, in those days, they believed in like 15 gods, so we are not sure who he is thinking. So this must be Cazalbigi.

Line 8

Another feature of interest is the 'moi' in the 'responds-moi'. The Italian does with a rather more effective repetition of the 'rispondi'. The second one is exactly a gem in the octave range it covers. Instead the French does not really repeat the cri-de-coeur. It has 'responds' on one line and 'responds-MOI' in the second. As if Eurydice could respond to someone OTHER than the inquirer.

line 9-10.

The (b) section of this second stanza offers a new introduction of a new proposition in the French text that is not covered in the original Italian. It's the line, "entends ma voix qui t'appelle". The Italian does with the 'husband' motif. After all, the play -- and especially the Monteverdi -- opens, effectively, with the WEDDING. This is some sort of 'honeymoon' in hell they are suffering. She possibly died a virgin. So, it is 'meant' that Orfeo sees himself as 'il tuo fedel'. The French introduces, hyperbolically, 'epoux' (spouse) and instead of sticking to the repetition of the 'ALWAYS' (pure) your faithful one (il tuo fedel) adds this point about 'hear my voice that calls for you'.

line 12.

While the rhyme in the next section in Italian is magisterial (speranza, avanza -- or 'avanza', 'speranza', rather) the French manages even perhaps better with the addition of a THIRD -ance ending word. So we have 'silence' (to match 'avanza') and 'esperance' which matches 'speranza' -- but it adds "quel souffrance'. Yet another 'exclamative'. When I write 'proper' exclamative I mean the use of the wh- pronoun followed by the noun. Quelle souffrance. When we say, "What beauty!", what do we mean? I contend that we mean something like "This is SOME beauty". I.e. the use of the interrogative pronoun in the exclamative use is quite a bother, pragmatic. It has the form of a question, but it's an exclamation, and what is 'exclaimed' is just IMPLICATED. What suffering! Meaning -- what?

line 13.

While we cannot say that the Italian text is structured in terms of LONG phrases, one of the longest, grammatical, is that 'avanza--speranza' one which ends with 'ne dal ciel'. I.e. the whole section is just ONE proposition. "I have no hope on earth or heaven", he is saying. Instead the French version prefers to cut the proposition short -- instead of the locative, 'in earth as in heaven' we find a new proposition, with, yes, another exclamative, 'quel tournment dechire mon coeur'.

---- Next: to locate in the classical literature -- of the Greeks preferably -- anything similar coming from the VOICE of "Orfeo".

Or something --.

I

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Rien n'égale mon malheur.

Che farò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che farò senza il mio ben? Rien n'égale mon malheur.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Je succombe à ma douleur.

II

(a)

Euridice! Euridice! Eurydice! Eurydice!

Oh Dio, rispondi! Réponds! Quel supplice!

Rispondi! Réponds-moi!

(b)

Io son pure il tuo fedel. C'est ton époux, ton époux fidèle.

Io son pure il tuo fedel. Entends ma voix qui t'appelle,

il tuo fedel. ma voix qui t'appelle.

III

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Rien m'égale mon malheur.

Che farò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che farò senza il mio ben? Rien m'égale mon malheur.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Je succombe à ma doleur.

IV

(a)

Euridice! Euridice! Euydice! Eurydice!

(b)

Ah, non m'avanza Mortel silence!

Più soccorso, più speranza Vaine esperance! Quelle souffrance!

Né dal mondo né dal ciel. Quel tourment déchire mon cœur.

V

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben? Rien m'egale mon malheur.

Che fafò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

che faro senza il mio ben Rien m'égale mon malheur.

Che farò? Dove andrò? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che farò senza il mio ben? J'ai succombe à ma doleur,

Senza il mio ben? à ma doleur,

Senza il mio ben? à ma doleur.

NOTES.

For what is worth (a lot, :) -- since you won't find this online, this far!) the strict comparison, line-by-line of Ranieri de' Calzabigi and Moline's translation, which Ricordi ignored when he omitted it in the 1889 edition. One may do with a strict analysis of 'performative' acts. The Italian version is all about 'rhetorical' questions, almost -- although not quite. Some say that Orfeo is a controversial figure. So, when he says, "What shall I do WITHOUT Eurydice?" he may MEAN it. As it happens, he became so disilussioned with women after this disgrace that it provoked the reaction by the Furies who dismember him. I understand this was the original Monteverdi ending which he was forced to adapt for the wedding of de Medici, or something.

lines 1-2.

So, to the 'question', "Che faro, dove andro?", the French offers a statement: "J'ai perdu mon Eurydice". (In fact, this has been parodied, elsewhere, as "J'ai TROUVE mon Eurydice"). Again, the second 'rhetoric' question ("Where will I go without my good?") becomes another statement, however spiritual, "Rien n'egale mon malheur".

lines 3-4.

The loveliness of the interrupted questions in the Italian, "What shall I do, where shall I go" (che faro, dove andro) are turned into 'exclamatives' in French. In fact, I find one exclamative too many in the French. So the first here are "Sort cruel!" corresponding to the abbreviated question, "Che faro", and the proper exclamative, "Quelle rigueur" for the "dove andro".

line 5.

The next divergence is the introduction of a NEW proposition in the first 'stanza', 'Je succombe a ma doleur' in the French. The Italian just does with a repetition of previous, er, questions, notably the second: "Dove andro senza il mio ben?".

line 5.

Now, we can examine the rhyme in the first stanza. The French manages with a perfect consonant rhyme in a trio: malheur--rigueur--douleur. Which is unavailable in Italian, which merely has, but I love it, still, 'mio ben', rhyiming with 'mio ben', rhyming with 'mio ben'!

line 6-7.

In the second 'stanza', Moline manages to introduce 'suplice' to rhyme with "Eurydice" of the 'vocative' (one vocative too many, for my taste, in this arietta). Instead, the Italian, rather clumsily, introduces a different emphatic, "Oh Dio", which sort of puts me off slightly. I do tend to use this exclamative often, but without MEANING it. How many of us, do say, "Oh my God" withOUT meaning it. I think this is the case with Orfeo. In any case, in those days, they believed in like 15 gods, so we are not sure who he is thinking. So this must be Cazalbigi.

Line 8

Another feature of interest is the 'moi' in the 'responds-moi'. The Italian does with a rather more effective repetition of the 'rispondi'. The second one is exactly a gem in the octave range it covers. Instead the French does not really repeat the cri-de-coeur. It has 'responds' on one line and 'responds-MOI' in the second. As if Eurydice could respond to someone OTHER than the inquirer.

line 9-10.

The (b) section of this second stanza offers a new introduction of a new proposition in the French text that is not covered in the original Italian. It's the line, "entends ma voix qui t'appelle". The Italian does with the 'husband' motif. After all, the play -- and especially the Monteverdi -- opens, effectively, with the WEDDING. This is some sort of 'honeymoon' in hell they are suffering. She possibly died a virgin. So, it is 'meant' that Orfeo sees himself as 'il tuo fedel'. The French introduces, hyperbolically, 'epoux' (spouse) and instead of sticking to the repetition of the 'ALWAYS' (pure) your faithful one (il tuo fedel) adds this point about 'hear my voice that calls for you'.

line 12.

While the rhyme in the next section in Italian is magisterial (speranza, avanza -- or 'avanza', 'speranza', rather) the French manages even perhaps better with the addition of a THIRD -ance ending word. So we have 'silence' (to match 'avanza') and 'esperance' which matches 'speranza' -- but it adds "quel souffrance'. Yet another 'exclamative'. When I write 'proper' exclamative I mean the use of the wh- pronoun followed by the noun. Quelle souffrance. When we say, "What beauty!", what do we mean? I contend that we mean something like "This is SOME beauty". I.e. the use of the interrogative pronoun in the exclamative use is quite a bother, pragmatic. It has the form of a question, but it's an exclamation, and what is 'exclaimed' is just IMPLICATED. What suffering! Meaning -- what?

line 13.

While we cannot say that the Italian text is structured in terms of LONG phrases, one of the longest, grammatical, is that 'avanza--speranza' one which ends with 'ne dal ciel'. I.e. the whole section is just ONE proposition. "I have no hope on earth or heaven", he is saying. Instead the French version prefers to cut the proposition short -- instead of the locative, 'in earth as in heaven' we find a new proposition, with, yes, another exclamative, 'quel tournment dechire mon coeur'.

---- Next: to locate in the classical literature -- of the Greeks preferably -- anything similar coming from the VOICE of "Orfeo".

Or something --.

Two-column format for "Che faro senza Euridice?"

I

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio been? Rien n'égale mon malheur

Che faro? Dove andro? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che faro senza il mio ben? Rien n'égale mon malheur.

Dove andro senza il mio ben? Je succombe à ma douleur.

II

Euridice! Euridice! Eurydice! Eurydice!

Oh Dio, rispondi! Réponds! quel supplice!

Rispondi! Réponds-moi!

Io son pure il tuo fedel. C'est ton époux fidèle.

Io son pure il tuo fedel. Entends ma voix qui t'appelle,

il tuo fedel. ma voix qui t'appelle.

III

Che faro senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andro senza il mio ben. Rien m'egale mon malheur

Che faro, dove andro Sorte cruel, quelle rigeur

Che faro senza il mio ben Rien m'egale mon malheur

dove andro senza il mio ben. Je succombe a mon doleur.

IV

Euridice! Euridice! Eyrydice! Eurydice!

Ah, non m'avanza Mortel silence!

più soccorso, più speranza Vaine esperance! Quelle souffrance!

né dal mondo né dal ciel. Quel tourment déchire mon cœur.

V

Che farò senza Euridice? j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben Rien m'egale mon malheur

Che faro? Dove andro? Sorte cruel! Quelle rigeur!

che faro senza il mio ben rien m'egale mon malheur

Che faro? Dove andro? Sort cruel! Quelle rigeur!

Che faro senza il mio ben? j'ai soccombe a mon doleur

senza il mio ben? a mon doleur

senza il mio ben? a mon doleur.

Che farò senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio been? Rien n'égale mon malheur

Che faro? Dove andro? Sort cruel! Quelle rigueur!

Che faro senza il mio ben? Rien n'égale mon malheur.

Dove andro senza il mio ben? Je succombe à ma douleur.

II

Euridice! Euridice! Eurydice! Eurydice!

Oh Dio, rispondi! Réponds! quel supplice!

Rispondi! Réponds-moi!

Io son pure il tuo fedel. C'est ton époux fidèle.

Io son pure il tuo fedel. Entends ma voix qui t'appelle,

il tuo fedel. ma voix qui t'appelle.

III

Che faro senza Euridice? J'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andro senza il mio ben. Rien m'egale mon malheur

Che faro, dove andro Sorte cruel, quelle rigeur

Che faro senza il mio ben Rien m'egale mon malheur

dove andro senza il mio ben. Je succombe a mon doleur.

IV

Euridice! Euridice! Eyrydice! Eurydice!

Ah, non m'avanza Mortel silence!

più soccorso, più speranza Vaine esperance! Quelle souffrance!

né dal mondo né dal ciel. Quel tourment déchire mon cœur.

V

Che farò senza Euridice? j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

Dove andrò senza il mio ben Rien m'egale mon malheur

Che faro? Dove andro? Sorte cruel! Quelle rigeur!

che faro senza il mio ben rien m'egale mon malheur

Che faro? Dove andro? Sort cruel! Quelle rigeur!

Che faro senza il mio ben? j'ai soccombe a mon doleur

senza il mio ben? a mon doleur

senza il mio ben? a mon doleur.

Line-by-line: Italian-French, Che faro senza Euridice, J'ai perdu mon Eurydice

I

Che farò senza Euridice.

j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

dove andrò senza il mio be-en.

rien n'égale mon malheur

che faro? dove andro?

sort cruel, quelle rigueur

che faro senza il mio ben

rien n'égale mon malheur.

dove andro senza il mio ben?

je succombe à ma douleur.

--- II

(a)

Euridice! Euridice!

Eurydice! Eurydice!

oh dio, rispondi,

réponds! quel supplice!

rispondi.

Réponds-moi!

(b)

io son pure il tuo fedel.

C'est ton époux fidèle.

io son pure il tuo fedel.

Entends ma voix qui t'appelle,

il tuo fedel.

ma voix qui t'appelle.

BACK TO I:

che faro senza Euridice?

j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

dove andro senza il mio bene.

rien m'egale mon malheur

che faro, dove andro

sorte cruel, quelle rigeur

che faro senza il mio be-e-ne

rien m'egale mon malheur

dove andro senza il mio ben.

j'ai succombe a mon doleur.

III

Euridice, Euridice.

Eyrydice! Eurydice!

(b)

Ah, non m'avanza più soccorso, più speranza

mortel silence! vaine esperance! quelle souffrance!

né dal mondo né dal ciel.

quel tourment déchire mon cœur.

--- IV -- back to I

che farò senza Euridice?

j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

dove andrò senza il mio ben

rien m'egale mon malheur

che faro, dove andro

sorte cruel, quelle rigeur

che faro senza il mio ben

rien m'egale mon malheur

che faro, dove andro

sort cruel, quelle rigeur

che faro senza il mio ben

j'ai soccombe a mon doleur

senza il mio ben

a mon doleur

senza il mio ben.

a mon doleur.

Che farò senza Euridice.

j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

dove andrò senza il mio be-en.

rien n'égale mon malheur

che faro? dove andro?

sort cruel, quelle rigueur

che faro senza il mio ben

rien n'égale mon malheur.

dove andro senza il mio ben?

je succombe à ma douleur.

--- II

(a)

Euridice! Euridice!

Eurydice! Eurydice!

oh dio, rispondi,

réponds! quel supplice!

rispondi.

Réponds-moi!

(b)

io son pure il tuo fedel.

C'est ton époux fidèle.

io son pure il tuo fedel.

Entends ma voix qui t'appelle,

il tuo fedel.

ma voix qui t'appelle.

BACK TO I:

che faro senza Euridice?

j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

dove andro senza il mio bene.

rien m'egale mon malheur

che faro, dove andro

sorte cruel, quelle rigeur

che faro senza il mio be-e-ne

rien m'egale mon malheur

dove andro senza il mio ben.

j'ai succombe a mon doleur.

III

Euridice, Euridice.

Eyrydice! Eurydice!

(b)

Ah, non m'avanza più soccorso, più speranza

mortel silence! vaine esperance! quelle souffrance!

né dal mondo né dal ciel.

quel tourment déchire mon cœur.

--- IV -- back to I

che farò senza Euridice?

j'ai perdu mon Eurydice.

dove andrò senza il mio ben

rien m'egale mon malheur

che faro, dove andro

sorte cruel, quelle rigeur

che faro senza il mio ben

rien m'egale mon malheur

che faro, dove andro

sort cruel, quelle rigeur

che faro senza il mio ben

j'ai soccombe a mon doleur

senza il mio ben

a mon doleur

senza il mio ben.

a mon doleur.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Che faro senza Euridice -- as sung by Schipa and Pavarotti

GLUCK, Orfeo (1764).

----- tenore.

------------------ rec. by Tito Schipa (with orchestra La Scala, 1932, L. Pavarotti, with piano acc. 1985)

---- DVD

piano introduction

---- vocal line:

che farò -- senza Euridice --

dove andrò -- senza il mio be-en.

che-e faro, dove-e andro

che faro senza el mio ben

do-o-ve andro se-enza il mio ben.

----

Euridice, Euridice

oh-dio -- rispondi,

---

rispo-o-o-o-ndi.

io son pure il tuo fedel.

io son pure il tuo fedel.

il tuo fed-e-l.

che faro senza Euridice

dove andro senza il mio bene.

che faro

dove andro

che faro senza il mio be-e-ne

dove andro senza il mio ben.

-----

Euridice -- Eu-u-u-ri-i-ce.

----

Ah- non m'avanza --- più soccorso

più speranza

né dal mondo ----- né-e-e-e-e- dal cie-e-e-e-l.

che farò senza Euridice

dove andrò senza il mio ben

che faro, dove andro

che faro senza il mio ben

che faro dove andro

che faro senza il mio bee-e--en

senza il mio be-e-e-n

senza il mio ben.

----- tenore.

------------------ rec. by Tito Schipa (with orchestra La Scala, 1932, L. Pavarotti, with piano acc. 1985)

---- DVD

piano introduction

---- vocal line:

che farò -- senza Euridice --

dove andrò -- senza il mio be-en.

che-e faro, dove-e andro

che faro senza el mio ben

do-o-ve andro se-enza il mio ben.

----

Euridice, Euridice

oh-dio -- rispondi,

---

rispo-o-o-o-ndi.

io son pure il tuo fedel.

io son pure il tuo fedel.

il tuo fed-e-l.

che faro senza Euridice

dove andro senza il mio bene.

che faro

dove andro

che faro senza il mio be-e-ne

dove andro senza il mio ben.

-----

Euridice -- Eu-u-u-ri-i-ce.

----

Ah- non m'avanza --- più soccorso

più speranza

né dal mondo ----- né-e-e-e-e- dal cie-e-e-e-l.

che farò senza Euridice

dove andrò senza il mio ben

che faro, dove andro

che faro senza il mio ben

che faro dove andro

che faro senza il mio bee-e--en

senza il mio be-e-e-n

senza il mio ben.

"Con che tenorita": With Gluck's "Orfeo" (del Globo) and Handel's "Serse" (Avenida), "Gli Operai" dedicate their fortnightly meeting to an examination of title roles regained for the tenor repertoire ("Che faro senza Euridice", "Ombra mai piu"). With Luigi Speranza at the piano. 5 pm. St. Michael Hall, Calle 58, No. 611, La Plata.

Sunday, September 5, 2010

Che faro senza Euridice: il tenore italiano gluckiano

by Luigi Speranza for "Gli Operai" jlsperanza@aol.com

--- as recorded by tenor N. Gedda:

J'ai perdu mon Eurydice,

Rien n'égale mon malheur;

Sort cruel! quelle rigueur!

Rien n'égale mon malheur!

Je succombe à ma douleur!

Eurydice, Eurydice,

Réponds, quel supplice!

Réponds-moi!

C'est ton époux fidèle;

Entends ma voix qui t'appelle.

J'ai perdu mon Eurydice, etc

Eurydice, Eurydice!

Mortel silence! Vaine espérance!

Quelle souffrance!

Quel tourment déchire mon cœur!

J'ai perdu mon Eurydice, etc

Ah! puisse ma douleur finir avec ma vie!

Je ne survivrai pas à ce dernier revers.

Je touche encor aux portes des enfers,

J'aurai bientôt rejoint mon épouse chérie.

Oui, je te suis, tendre objet de ma foi,

Je te suis, attends-moi!

Tu ne me seras plus ravie,

Et la mort pour jamais va m'unir avec toi.

--- as recorded by tenor N. Gedda:

J'ai perdu mon Eurydice,

Rien n'égale mon malheur;

Sort cruel! quelle rigueur!

Rien n'égale mon malheur!

Je succombe à ma douleur!

Eurydice, Eurydice,

Réponds, quel supplice!

Réponds-moi!

C'est ton époux fidèle;

Entends ma voix qui t'appelle.

J'ai perdu mon Eurydice, etc

Eurydice, Eurydice!

Mortel silence! Vaine espérance!

Quelle souffrance!

Quel tourment déchire mon cœur!

J'ai perdu mon Eurydice, etc

Ah! puisse ma douleur finir avec ma vie!

Je ne survivrai pas à ce dernier revers.

Je touche encor aux portes des enfers,

J'aurai bientôt rejoint mon épouse chérie.

Oui, je te suis, tendre objet de ma foi,

Je te suis, attends-moi!

Tu ne me seras plus ravie,

Et la mort pour jamais va m'unir avec toi.

Il tenore italiano gluckiano

by Luigi Speranza for "Gli Operai" jlsperanza@aol.com

Recordings of "Orfeo" 1774 Paris version (with tenor Orpheus)

Léopold Simoneau

(Philips mono, 1956 - reissued on CD 2001)

Nicolai Gedda

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire,

Louis de Fremont

Deutsche Grammophon, mono, 1955 - reissued on CD by Profil 2009)

Jean-Paul Fouchécourt

Naxos 2002

Richard Croft

Deutsche Grammophon Archiv, 2002, released 2004

J. D. Florez

Decca 2010

David Hobson

1993, (OpusArte/Faveo and Kultur 2006).

Recordings of "Orfeo" 1774 Paris version (with tenor Orpheus)

Léopold Simoneau

(Philips mono, 1956 - reissued on CD 2001)

Nicolai Gedda

Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire,

Louis de Fremont

Deutsche Grammophon, mono, 1955 - reissued on CD by Profil 2009)

Jean-Paul Fouchécourt

Naxos 2002

Richard Croft

Deutsche Grammophon Archiv, 2002, released 2004

J. D. Florez

Decca 2010

David Hobson

1993, (OpusArte/Faveo and Kultur 2006).

Saturday, September 4, 2010

Che faro senza Euridice? In search for Orfeo the tenor

by Luigi Speranza for "Gli Operai" jlsperanza@aol.com

--- to accompany production at "Il Globo".

"Orfeo ed Euridice ("Orphée et Eurydice") is an opera composed by Christoph Willibald Gluck based on the myth of Orfeo, set to a libretto by Ranieri de' Calzabigi."

"It belongs to the genre of the "azione teatrale," meaning an opera on a mythological subject with choruses and dancing.[1]

"The piece was first performed at Vienna on 5 October 1762."

""Orfeo ed Euridice" is the first of Gluck's "reform" operas, in which he attempted to replace the abstruse plots and overly complex music of opera seria with a "noble simplicity" in both the music and the drama.[2]

"The opera is the most popular of Gluck's works,[2] and one of the most influential on subsequent German opera."

"Variations on its plot—the underground rescue-mission in which the hero must control, or conceal, his emotions—include Mozart's The Magic Flute, Beethoven's Fidelio and Wagner's Das Rheingold."

"Though originally set to an Italian libretto, Orfeo ed Euridice owes much to the genre of French opera, particularly in its use of

accompanied recitative

and a general absence of vocal virtuosity."

"Indeed, 12 years after the 1762 premiere, Gluck re-adapted the opera to suit the tastes of a Parisian audience at the Académie Royale de Musique with a libretto by Pierre-Louis Moline."

"This reworking was given the title Orphée et Eurydice, and several alterations were made in vocal casting and orchestration to suit French tastes."

"Francesco Algarotti's Essay on the Opera (1755) was a major influence in the development of Gluck's reformist ideology.[3]"

"Algarotti proposed a heavily simplified model of opera seria, with the drama pre-eminent, instead of the music or ballet or staging. The drama itself should "delight the eyes and ears, to rouse up and to affect the hearts of an audience, without the risk of sinning against reason or common sense"."

"Algarotti's ideas influenced both Gluck and his librettist, Calzabigi.[4] Calzabigi was himself a prominent advocate of reform,[2] and he stated as follows."

""If Mr Gluck was the creator of dramatic music, he did not create it from nothing. I provided him with the material or the chaos, if you like. We therefore share the honour of that creation."[5]

"Other influences included the composer Niccolò Jommelli and his maître de ballet at Stuttgart, Jean-Georges Noverre.[4]

"Noverre's Lettres sur la danse (1760) called for dramatic effect over acrobatic ostentation; Noverre was himself influenced by the operas of Rameau and the acting style of David Garrick.[4]

"The considerable quantity of ballet in Orfeo ed Euridice is thought to be due to his influence. Jommelli himself was noted for his blending of all aspects of the production: ballet, staging, and audience.[6]"

Italian Premiere Cast

5 October 1762

(Conductor: - ) Revised version

French Premiere Cast

2 August 1774

(Conductor: - )

Orfeo Alto castrato (Vienna),

High tenor, Haute-contre (Paris),

or mezzo-soprano

Gaetano Guadagni

Joseph Legros

Amore soprano

Marianna Bianchi Sophie Arnould

Euridice soprano Lucia Clavereau Rosalie Levasseur

The first lines of arias, choruses, etc., are given in Italian (1762 version) and French (1774 version).

Atto 1. A chorus of nymphs and shepherds join Orfeo around the tomb of his wife Euridice in a solemn chorus of mourning; Orfeo is only able to utter Euridice's name (Chorus and Orfeo:

“Ah, se intorno”/“Ah! Dans ce bois”).

Orfeo sends the others away and sings of his grief in the aria

"Chiamo il mio ben"/“Objet de mon amour”,

the three verses of which are preceded by expressive recitatives. This technique was extremely radical at the time and indeed proved overly so for those who came after Gluck: Mozart chose to retain the unity of the aria. Amore (Cupid) appears, telling Orfeo that he may go to the Underworld and return with his wife on the condition that he not look at her until they are back on earth (1774 only: aria by Amour,

“Si les doux accords”). As encouragement, Amore informs Orfeo that his present suffering shall be short-lived with the aria

"Gli sguardi trattieni"/“Soumis au silence”.

Orfeo resolves to take on the quest. In the 1774 version only he delivers an ariette

("L'espoir renaît dans mon âme") in the older, showier, Italian style, originally composed for an occasional entertainment, Il Parnaso confuso (1765), and subsequently re-used in another one, Le feste d'Apollo (1769).[1]

Atto II.

In a rocky landscape, the Furies refuse to admit Orfeo to the Underworld, and sing of Cerberus, its canine guardian

(“Chi mai dell’Erebo”/“Quel est l’audacieux”).

When Orfeo, accompanied by his lyre (represented in the opera by a harp), begs for pity in the aria

"Deh placatevi con me"/“Laissez-vous toucher”,

he is at first interrupted by cries of "No!" from the Furies, but they are eventually softened by the sweetness of his singing in the arias

"Mille pene"/“Ah! La flamme and "Men tiranne"/“La tendresse”, and let him in

(“Ah, quale incognito affetto”/“Quels chants doux”).

In the 1774 version, the scene ends with the "Dance of the Furies" (No. 28).[7]

The second scene opens in Elysium. The brief ballet of 1762 became the four-movement "Dance of the Blessed Spirits" (with a prominent part for solo flute) in 1774. This is followed (1774 only) by a solo which celebrates happiness in eternal bliss (“Cet asile”), sung by either an unnamed Spirit or Euridice, and repeated by the chorus. Orfeo arrives and marvels at the purity of the air in an arioso

("Che puro ciel"/“Quel nouveau ciel”).

But he finds no solace in the beauty of the surroundings, for Euridice is not yet with him. He implores the spirits to bring her to him, which they do (Chorus:

“Torna, o bella”/“Près du tendre objet”).

Atto III

On the way out of Hades, Euridice is delighted to be returning to earth, but Orfeo, remembering the condition related by Amore in Act I, lets go of her hand and refuses to look at her, does not explain anything to her. She does not understand his action and reproaches him, but he must suffer in silence (Duet:

“Vieni, appaga il tuo consorte”/“Viens, suis un époux”).

Euridice takes this to be a sign that he no longer loves her, and refuses to continue, concluding that death would be preferable. She sings of her grief at Orfeo's supposed infidelity in the aria "Che fiero momento"/“Fortune ennemie” (in 1774, there is a brief duet before the reprise). Unable to take any more, Orfeo turns and looks at Euridice; again, she dies. Orfeo sings of his grief in the famous aria

Che farò senza Euridice?

J’ai perdu mon Eurydice

(“What shall I do without Euridice?”/"I have lost my Euridice")

Orfeo decides he will kill himself to join Euridice in Hades, but Amore returns to stop him (1774 only: Trio: “Tendre Amour”). In reward for Orfeo's continued love, Amore returns Euridice to life, and she and Orfeo are reunited. After a four-movement ballet, all sing in praise of Amore (“Trionfi Amore”). In the 1774 version, the chorus (“L’Amour triomphe”) precedes the ballet, to which Gluck had added three extra movements.

The opera was first performed in Vienna at the Burgtheater on 5 October 1762, for the name-day celebrations of the Emperor Francis I.

The production was supervised by the reformist theatre administrator, Count Giacomo Durazzo.

Choreography was by Gasparo Angiolini, and set designs were by Giovanni Maria Quaglio, both leading members of their fields.

The first Orfeo was the famous castrato Gaetano Guadagni.

Orfeo was revived in Vienna during the following year, but then not performed until 1769.

For the performances that took place in London in 1770, Guadagni sang the role of Orfeo, but little of the music bore any relation to Gluck's original, with J.C. Bach - "the English Bach" - providing most of the new music.[2]

Haydn conducted a performance of the Italian version at Eszterháza in 1776.

During the early 19th century, Adolphe Nourrit became particularly well-known for his performances of Orfeo at the Paris Opera.

In 1854 Franz Liszt conducted the work at Weimar, composing a symphonic poem of his own to replace Gluck's original overture.[2]

Typically during the 19th century and for most of the 20th century, the role of Orfeo was sung by a female contralto, and noted interpreters of the role from this time include Clara Butt and Kathleen Ferrier, and the mezzo-sopranos Rita Gorr, Marilyn Horne, Janet Baker and Risë Stevens (at the Metropolitan Opera).[2]

Among conductors, Arturo Toscanini was a notable proponent of the opera.[2] His radio broadcast of Act II was eventually released on both LP and CD.

In 1769 for a performance at Parma which was conducted by the composer,[2] Gluck transposed the role of Orfeo up for the soprano castrato Giuseppe Millico, maintaining a libretto in Italian.

This version has not been performed in modern times.[2]

Gluck revised the score again for a production in Paris, which premiered on 2 August 1774.

This version, named Orphée et Eurydice, had a French libretto by Pierre-Louis Moline, which was both a translation of and an expansion upon Calzabigi's original text.

Gluck expanded and rewrote parts of the opera, and changed the role of Orfeo from a part for a castrato to one for high tenor or the so-called haute-contre - the usual voice in French opera for heroic characters - as the French almost never used castrati.[2]

This version of the work also had additional ballet sequences, conforming to the tastes that were prevalent at the time in Paris.

In 1859, the composer Hector Berlioz made a version of the opera - in four acts - with the singer Pauline Viardot in mind, adapting the score for a female alto.[8]

In this adaptation, Berlioz used the key scheme of the 1762 Vienna score while incorporating much of the additional music of the 1774 Paris score.

He returned to the Italian version only when he considered it to be superior either in terms of music or in terms of the drama.[8]

He also changed the orchestration to take advantage of new developments in musical instruments.[8]

In Berlioz's day, Orfeo came to be generally sung by a female alto or

a tenor,

as the original version for castrato became increasingly neglected.

Operatic castrati themselves had virtually vanished by 1825, and performances of the original version for castrato became increasingly rare.

The modern practice of approximating castrati by using countertenors as replacements only dates to 1950.[2]

Finally, an 1889 edition, published by Ricordi, combined elements of both the Italian and the French versions, using again a female alto as Orfeo.

This edition proved extremely popular, and consisted largely of Berlioz's adaption condensed into three acts.

It also re-incorporated much of the music of the 1774 French version that had been omitted by Berlioz.

On occasion the role of Orfeo has even been transposed down an octave for a baritone to sing.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Hermann Prey are two notable baritones who have performed the role in Germany.[2]

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau recorded the opera, a recording which is still available commercially.

The opera was the first by Gluck showing signs of his ambition to reform opera seria. Self-contained arias and choruses make way for shorter pieces strung together to make larger structural units. Da capo arias are notable by their absence;[2]

Gluck instead uses strophic form, notably in Act One's "Chiamo il mio ben così", where each verse is interposed with dramatic recitative, - that is, stromentato, where the voice is accompanied by part or all of the orchestra - and rondo form, such as in Act Three's famous

"Che farò senza Euridice?".

Also absent is traditional secco recitative, where the voice is accompanied only by the basso continuo.[2]

On the whole, old Italian operatic conventions are disregarded in favour of giving the action dramatic impetus.

The complexity of the storyline is greatly reduced by eliminating subplots. Gluck was influenced by the example of French tragédies en musique, particularly those of Rameau. Like them, the opera contains a large number of expressive dances, extensive use of the chorus and accompanied recitative.[2]

The coup de théâtre of opening the drama with a chorus mourning one of the main characters is very similar to that used in Rameau's Castor et Pollux (1737).[9]

Other elements do not follow Gluck's subsequent reforms; for instance, the brisk, cheerful overture does not reflect the action to come.[2]

The role of Orfeo calls for an especially gifted actor, so that the strophic "Chiamo il mio ben così" does not become dull, and so that tragic import can be given both to this aria and to

"Che farò senza Euridice?", both of which are based on harmonies that are not obviously mournful in nature.[10]

The first Orfeo, Gaetano Guadagni, was reputedly a fine actor who had certainly taken lessons while in London from the renowned Shakespearian actor David Garrick.

Guadagni was apparently also able to project a moving and emotive tone without raising his voice.[10]

Indeed, Gluck faced criticism of "Che farò senza Euridice?" on the grounds that it was emotionally uninvolved;

he responded by pointing out the absolute necessity of fine execution of the aria:

"make the slightest change, either in the movement or in the turn of expression, and it will become a saltarello for marionettes".[10]

Gluck's reforms, which began with Orfeo ed Euridice, have had significant influence throughout operatic history. Gluck's ideals heavily influenced the popular works of Mozart, Wagner, and Weber,[11] with Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk vision especially influenced by that of Gluck.[12]

Old-style opera seria and the domination of embellishment-orientated singers came to be increasingly unpopular after the success of Gluck's operas as a whole and Orfeo in particular.[2]

In Orfeo ed Euridice the orchestra is far more predominant than in earlier opera, most notably in Orfeo's arioso "Che puro ciel". Here the voice is reduced to the comparatively minor role of recitative-style declamation, while the oboe carries the main melody, supported by solos from the flute, cello, bassoon, and horn. There is also accompaniment from the strings (playing in triplets) and the continuo in the most complex orchestration that Gluck ever wrote.[2]

Gluck made a number of changes to the orchestration of Orfeo when adapting it from the original Italian version to the French version of 1774.

Cornetts and chalumeaux are replaced by commoner and more modern oboes and clarinets, while the part played by trombones considerably decreases, possibly due to a lack of technical ability on the part of the French trombonists.[5] Cornetts were instruments that were typically used for church music, and chalumeaux were predominant only in chamber music: both cornetts and chalumeaux were unpopular in France in 1774.[5]

In many ways the change from chalumeau to oboe corresponds to that from castrato to high tenor.[5]

Neither castrato nor chalumeau were to survive.[5]

In both the Italian and French version Orfeo's lyre is represented by the harp, and it was this use of the instrument in 1774 that it is usually thought introduced the harp to French orchestras.[5]

Each verse of the strophic "Chiamo il mio ben cosi" is accompanied by different solo instruments.